This last week has seen much media attention and online mirth concerning the discovery of horse meat in certain high street beef products on sale throughout Ireland and the UK. For a good round-up of the initial reports, see Slugger O’Toole’s post here which contains the following quote from the Chief Executive of FSAI:

“In Ireland, it is not in our culture to eat horsemeat and therefore, we do not expect to find it in a burger…”

The concept of a deep-seated cultural and/or religious abhorrence of horse meat within modern Ireland and Britain struck me as extremely interesting. The disgust expressed in some quarters over the thought of inadvertently ingesting the same reminded me of certain historical and archaeological parallels within our shared cultural legacy.

As far back as the early medieval period, there are indications that both insular and European ecclesiastical authorities not only disapproved of the practice, but actively engaged in efforts to dissuade others from partaking of the same. So apparently successful was this early Christian disparagement, that todays cultural condemnation could perhaps be argued as not only being derived from an early medieval repugnance towards horseflesh consumption; but perhaps even, an underlying revulsion to what it may have represented to early Christian mindsets.

Early Christian Taboo

Around 731 AD, Pope Gregory III prohibited the eating of horse meat, calling it “an unclean and execrable act.” He did so in a letter to Boniface ‘Apostle to the Germans’, whose missionary activity seems to have encountered problems with the custom. Despite the papal decree, it seems the Germans did not immediately heed the warning. Boniface later communicated to Pope Zachary I that the practice remained a barrier to conversion. In a penitential of Bishop Ecgbert, the Bishop of York (and a close contemporary of Boniface and Gregory) we find evidence that although horseflesh was not strictly prohibited in his particular area of Britain; the custom was most certainly frowned upon and decent families would not lower themselves to even buy it.

The late seventh century AD Vita Columba (Life of St. Columba) presents the idea of eating the flesh of a mare as an unworthy idea, associated with thieves and unworthy penitents; while the eight century Collectio Canonum Hibernensis (Collection of Irish Canon law) supplies a fairly drastic penance of three and a half years on bread and water for those (ecclesiastics) confessing to have consumed horseflesh.

The Bretha Crólige an eight century secular Irish law tract dealing with injury and sick maintainance supplies a slightly different ‘medicinal’ perspective. Regarding horseflesh, it states that it is ‘not right to give it to any one who is in the depths of sickness‘ as it had a tendency to ‘stir up sickness in the stomach of wounded heroes‘. While not exactly as damning as those previous, such ‘advice’ does not necessarily rank as positive for the average medieval consumer. (If horseflesh made the likes of Cúchulainn sick, what would it do to a lesser mortals?) In terms of literary metaphor, the association here of ‘heroes/warriors’ may in fact reflect a similar if indirect concern as that espoused by Christian authorities (of which I will return to later).

Such early historical evidence indicates that by the seventh/eight centuries AD onwards, the practice/tradition of horseflesh consumption was of sufficient concern to warrant high status ecclesiastical reproach. But what exactly were they so concerned about? And what precisely was so offensive about horse-flesh that made it such a taboo meat within early medieval Christianity? Before taking the bit between my teeth (sorry!); we need to go on somewhat of a diversion…

The Horse in Late Prehistoric Europe

The horse throughout prehistory was naturally an important and valuable tool for transport and traction. Then, as now, horses were a relatively exclusive and expensive possession; limited for the most part to high status individuals and societal elites. As such, horses, particularly when not in use for mundane work would have been a powerful symbol of wealth and prestige in life; and it is perhaps no surprise to find them occupying a similar position in death. Within the archaeological record of central and northern Europe in late prehistory, horses and equine related paraphernalia seem to have been considered appropriate grave goods for extremely high status individuals.

Horses and their trappings: the burial evidence

Although rare, the evidence for richly furnished chariot/horse/human burials where they do occur in the European Iron Age is particularly spectacular. Continental sites, such as Attichy, and Vix, France; and Hochdorf, Germany are well-known in the chariot themed literature; while horse burial in Scandanavian and Baltic regions during the Iron Age is also well attested. Closer to home similar chariot graves are known from Iron Age Britain, mostly within the region associated with the Arras Culture in modern-day Yorkshire, such as the famous example at Wetwang; but occasionally found elsewhere, such as at Newbridge, Scotland.

Several more human/horse depositions/burials are also known from early medieval/Anglo-Saxon Britain and Europe (such as Mound 17 at Sutton Hoo and Wulfsen in Germany), suggesting that a ritual conceptual association with Horses and Burial/Deposition stretched across several northern European cultures and periods leading up to their respective Christianization phases. A particularly interesting aspect of these later phases of activity is the interpretation of ritual feasting at many such sites.

Horse Motif & Sacral Kingship

The close association of all the above with high status figures, almost certainly the ranking nobility and royalty of their day; indicates that horse symbolism, status and occasional sacrifice was apparently linked with ritual and performative expressions of kingship and power. This has been previously argued as reflecting remnants of a particularly ancient Proto-Indo-European cosmological system involving the celebration and metaphorical union between horse and king. Certainly, there are common residual motifs and attributes across a range of individual cultures of the late Iron Age/early medieval periods which have strong parallels with aspects of Vedic ritual and the ancient Roman festival of Equus October. Such apparent widespread distribution and residual survival, even allowing for substantial corruption, nevertheless suggests that the horse, both physically and metaphorically, played a role in European kingship/status rituals prior to Christianisation.

The archaeological evidence for such kingship/horse expression so far, has been almost exclusively linked with the burial evidence for the period; and yet it should be remembered that in this, we are only glimpsing the ‘endpoint’ of an individual royal reign. If the horse was a powerful symbol in pagan kingship ritual; then we can perhaps assume that it played a similar role within royal inauguration, authority and rule. We need look no further then insular Iron Age coins to see a particularly appropriate range of evidence that points towards the importance of horse symbolism, iconography and kingship.

Royal Iconography: Iron Age Coins

A remarkably common motif found on Insular Gaulish and British coins of the period is that of the horse, horse/human, and/or chariots & wheels. Certain British examples even combine abstract horse imagery with inscribed text; utilising the stylised ears and legs of horses into the character letters of the word/words involved. Such coins of the period were undoubtedly expressions of royal power, commissioned by local kings and chieftains, to both commemorate and consolidate their authority. The widespread choice and use of the horse as a visual motif and icon representing such power, is in itself, valuable Iron Age evidence for its underlying ritual symbolism behind the desire to portray royal/tribal wealth and prosperity.

Horse related ritual in Iron Age Ireland

Unfortunately, the evidence for equine based ritual activity in Iron Age Ireland is few and far between; with no comparable coin, chariot or burial culture surviving. Some elaborate and decorated metal Horse Bits from the period have been found, as well as several examples of so-called ‘Y-shaped bronze pendants’ (interpreted as horse trappings/equipment); testifying at least to a certain level of status connected with public display. Such horse paraphernalia, although rare, is thought to have played some part in Iron Age kingship ritual activity and expression associated with tribal boundaries.

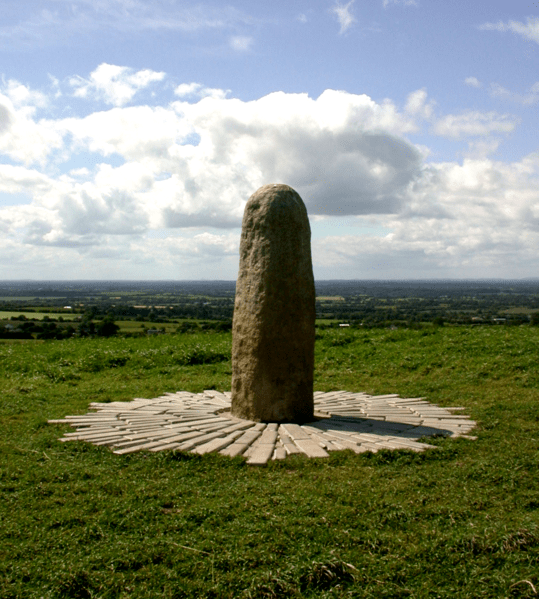

In terms of percentages in faunal assemblages, the highest recorded numbers of horse bones seemingly occur, intriguingly, on extremely high status ceremonial sites such as Tara (Co. Meath) and Dún Ailinne (Co. Kildare); both of which were linked with regional kingship and inauguration in the early medieval period . The horse bones from a ditch near the Mound of the Hostages at Tara, in particular, show evidence of being deliberately broken up with the marrow extracted; with other examples exhibiting knife cuts and roasting marks. Clearly, there seems to have been the occasional horse consumption on site; potentially associated with ritual feasting and possibly related to inauguration events.

Kingship & Tara

Tara being the pre-eminent ‘royal’ site of Ireland carries significant metaphorical currency, albeit from much later medieval literature. The site is depicted as an important inauguration site for regional and quasi-national kingship within early Irish sources. Interesting parallels with Proto-European kingship ritual attributes include the symbolic union of the king with a female sovereignty goddess and his legitimacy re-inforced by the act and skill of screeching chariot wheels (pulled by unharnessed horses) against certain monuments on site. It is not that difficult to imagine such early medieval motifs being indicative of older traditions, myths and symbolism stretching back into late prehistory. At the very least, such literary evidence points to an early medieval re-imagining of the past utilising similar cultural metaphors.

Early Medieval Horse Consumption: The Archaeological Evidence

The early medieval faunal evidence for Irish horse consumption is not dissimilar to that of the Iron Age. Authorities on the matter suggest that horse remains make up about 1-2% of bone assemblages on some higher status secular habitation sites. Certainly, where they can be sampled, they are found at sites associated with regional and local kingship, such as Knowth, Co. Meath and at Ballinderry Crannóg, Co. Westmeath. Another Crannóg at Moynagh Lough, Co. Meath, like that of Tara, provides evidence of horse bones that contain signs of marrow extraction and cut marks. Interestingly, the bones there seem to represent older animals, presumably at the end of their working lives.

Such evidence provides us with a picture of horses in use by (as to be expected) higher status elites in early medieval Ireland; and certainly those wealthy enough (or desperate enough) to perhaps have resorted to such animals during occasions of severe food shortages. It makes no economic sense to eat a valuable tool/transport/traction mechanism, unless one cannot help it. The extremely low percentages of early medieval horse bones in such assemblages suggest it was a relatively rare occurrence; and such evidence, where we can detect it, appears to indicate that consumption on certain sites may have been out of necessity rather than choice.

This is perhaps better illustrated by similar evidence for (small amounts of) horse consumption on early monastic sites such Moyne, Co. Mayo, Church Island & Illaunloughan, Co. Kerry and Iona in Scotland. With the exception of the first example, all are island monasteries. Despite the early historical evidence of severe penance for horseflesh consumption (above); it seems Irish monks were not immune to the same pitfalls occasionally suffered by the rest of the population. During times of famine and shortage, they too apparently resorted to eating horse meat regardless of ecclesiastical censure.

Horse & Kingship Motif in Early Irish Hagiography

If the Irish archaeological evidence shows us that horsemeat consumption wasn’t exactly a large and widespread problem; then the question arises as to why it appeared to cause a problem for Christian authorities. Ecclesiastical scholarly culture of the time provides us with intriguing connections and symbolism that may shed some light on the matter. Indeed, some of the earliest Patrician hagiography supplies us with the beginnings of what seems to be an ecclesiastical counter offensive prior to the eight century. Muirchú’s Life of Patrick, written in the late seventh century AD is a particularly fine example. Primarily written to promote Armagh as the central authority for the emerging cult of St. Patrick, he indulges in some very interesting horse symbolism concerning the pseudo-origins of the church at Armagh. Although long, it is worth quoting in full to get an idea of the context:

There was a wealthy and honoured man in the territory of Airther, whose name was Dáire. Holy Patrick asked him to give him a place wherein to worship, and the wealthy man said to the holy man: ‘Which place do you want?’ ‘I am asking’, the holy man said,’to be given that hill which is called Druim(m) Sailech, and that I may settle there.’ He, however, did not want to give the holy man that lofty place, but gave him another place, lower down, where there is now the Burial-Ground of the Martyrs beside Armagh, and there holy Patrick lived with his followers.

After some time a groom of Dáire’s came with his master’s horse to let it graze in the meadow of the Christians, and Patrick was offended by the release of the horse in his place, and said: ‘Dáire has behaved foolishly in sending brute animals to disturb the small place which he has given to God.’ The groom, however, listened as little as if he were deaf, and like one who is dumb he did not open his mouth to speak, but left the horse there over night and went away. Next day in the morning the groom came to look after the horse and by that time found it dead. He went home sadly and said to his master: ‘Look, that Christian has killed your horse because it displeased him that his place was disturbed’, and Dáire said: ‘He also shall be killed. Go ye now and kill him.’

The very moment his men went out sudden death struck Dáire, and his wife said: ‘This death is because of the Christian. Let somebody go at once and bring us his favours, and you will be well; and let those who have gone out to kill the Christian be stopped and told to return.’ Two men, then, went out and said to him, concealing from him what had actually happened: ‘Look, Dáire has fallen ill. Give us something to bring him by which he may be healed.’ Holy Patrick, however, knowing what had happened, said: ‘Is that so?’ blessed water and gave it to them, saying: ‘Sprinkle some of this water over your horse and take it with you.’ And they did so and the horse revived, and they took it away with them, and when the holy water was sprinkled over Dáire he was healed. After this Dáire went out to honour holy Patrick, bringing with him a marvellous bronze cauldron from overseas which held three measures, and Dáire said to the holy man: ‘Look, this cauldron shall be yours.’

Muirchú’s Life of St. Patrick, I.24 (1-10)

The episode is depicted as taking place at a Fertae burial site; late prehistoric/early medieval burial mounds which are occasionally depicted as suitable venues for inaugurations and legal gatherings. The figure of Daire clearly represents secular authority. The symbolic leading (and leaving!) of horses on land is mentioned within Early Irish legal texts dealing with procedures of formal entry and legal distraint. So the metaphorical background to the entire episode is firmly framed within well-known insular motifs. To an early medieval audience, it would have been clear that the narrative of the story revolved around a conflict between secular and Christian authority over possession and legitimacy.

The secondary location initially granted to the saint comes under threat by secular authority and procedure; both of which are symbolised by the horse. The death of the horse (extension of the Kings power) and the death of Daire (the kingly figure) are divine/saintly punishments for their transgressions. Their subsequent resurrection at the saints bequest illustrates Christian righteousness and power; ultimately recognised and acknowledged by Daire with a gift of submission of the large cauldron.

Armagh: A One-Horse Town

The episode not only utilises some common early Irish literary metaphors, but also illustrates the extent to which the emerging Christian culture harnessed traditional motifs of sacral kingship. In portraying Patrick in such terms and metaphors, Muirchú was infusing hagiography with a subtextual layer of insular legal precedent and authority; a fitting framework to depict the very foundation of a primatial See. (Indeed, even a later medieval origin story behind Armagh’s original Irish name, Ard Macha, was steeped in horse symbolism; with the mythological character Macha [See also: the Welsh Rhiannon and European Epona] involved in a victorious race with a kings chariot horses).

What is most interesting from our current perspective is the depicted associated components involved in the episode: an iron age/early medieval mound associated with kingship, the formal procession, display and subsequent death of a horse and the follow-up gift of a cauldron presented to the saint. The presence of all of these ‘ingredients’ at the heart of the (seventh century) story illustrates an early attestation and utilisation of such motifs centuries before some of the better known Irish examples which follow.

(To be continued…)

Bibliography

Bieler, L. (1975) The Irish Penitentials. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin.

Binchy, D.A.(1938) ‘Bretha Crólige’, Ériu , 12, 1-77

Bhreatnach, E. (1995) Tara: a select bibliography. Royal Irish Academy for the Discovery Programme, Dublin.

Bray, D. (1999) ‘Sacral Elements of Irish Kingship’, in Cusack, C. & Oldmeadow, P (eds.) This Immense Panorama: Studies in Honour of Eric J. Sharpe. Sydney Studies in Religion, University of Sydney, 105-116.

Carey, J. (2008) ‘From David to Labraid: sacral kingship and the emergence of monotheism in Israel and Ireland, in: Ritari, K. & and Bergholm, A. (eds) Approaches to religion and mythology in Celtic studies. Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2–27.

Creighton, J. (2000) Coins and Power in Late Iron Age Britain. Cambridge University Press.

Cross, P. J. (2011) ‘Horse Burial in First Millennium AD Britain: Issues of Deposition’, European Journal of Archaeology 14, 190–209.

De Jersey, P. (1996) Celtic Coinage in Britain (Shire Archaeology 72). Shire Publishing.

Doherty, C. (2005) ‘Kingship in Early Ireland’ in: Bhreathnach, E (eds). The kingship and landscape of Tara. Dublin, Four Courts Press, 3-29.

Edwards, N. (1990) The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland. London: BT Batsford.

Gleeson, P. (2012) ‘Constructing Kingship in Early Medieval Ireland: Power, Place and Ideology’, Medieval Archaeology 56, 1-33.

Gleize, Y. & Scuiller, C. & Armand, D. (2010) ‘An unusual Late Antique funerary deposit with equid remains (Usseau, France)’, Antiquity 84 (325), 765-773.

Godfrey, J. (1962) The Church in Anglo Saxon England. Cambridge University Press

Kelly F. (1997) Early Irish Farming. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

McCormick F. (2007) ‘The horse in early Ireland’, Anthropozoologica 42 (1), 85-104.

McCormick, F. (2009) “Ritual feasting in Iron Age Ireland” in G. Cooney, Katarina Becker, J. Coles, M. Ryan and S. Sievers (eds.) Relics of old decency: archaeological studies in later prehistory, Festschrift for Barry Raftery. Bray, Wordwell, 405-412.

Ni Chathain, P. (1991) ‘Traces of the cult of the horse in early Irish sources’, Journal of Indo-European Studies 19, 123-131.

Shenk, P. (2002) To Valhalla by Horseback? Horse Burial in Scandinavia during the Viking Age, Master’s Thesis in Nordic Viking and Medieval Culture, University of Oslo. Available at: https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/123456789/26678/7064.pdf?sequence=1

Sikora, M. ‘Diversity in Viking Age horse burial: a comparative study of Norway, Iceland, Scotland and Ireland’, Journal of Irish Archaeology 12/13, 87-109.

Simmons, F. J. (1994) Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Skvorzov, K. (2009) ‘Burials of Riders and Horses dated to the Roman Iron Age and Great Migration Period in Aleika-3 cementery on the Sambian peninsula’, Archaeologia Baltica 11, 130-148.

+++

Pingback: No Horses for Courses: Christian Horror of Horseflesh in Early Medieval Ireland [Part 3] | vox hiberionacum